Around January 5, 1922, Lila Murry, a 25-year old Nebraska native, discovered she was pregnant. Undoubtedly faced with limited options, Murry relocated from Lincoln, Nebraska to the Salvation Army Rescue Home in Omaha. The Rescue Home opened in 1896 and was self-characterized as a refuge for young and unwed pregnant women and girls, those regarded as “incorrigible,” who turned to the home for shelter and support. The women and girls received housing, medical assistance, and food, in addition to material items for the care of their child(ren). After giving birth, the women and girls were required to remain at the home for at least three months in order to “rescue their souls”, a process which occurred through religious training. The Home served as a pillar for these “fallen women,” housing 145 girls and overseeing 61 births in 1919. To fund such a mission, the Home frequently called on the support of Omaha’s upper-class social groups, such as the Washington Girls’ club as well as the Omaha chapter of Daughters of the American Revolution.

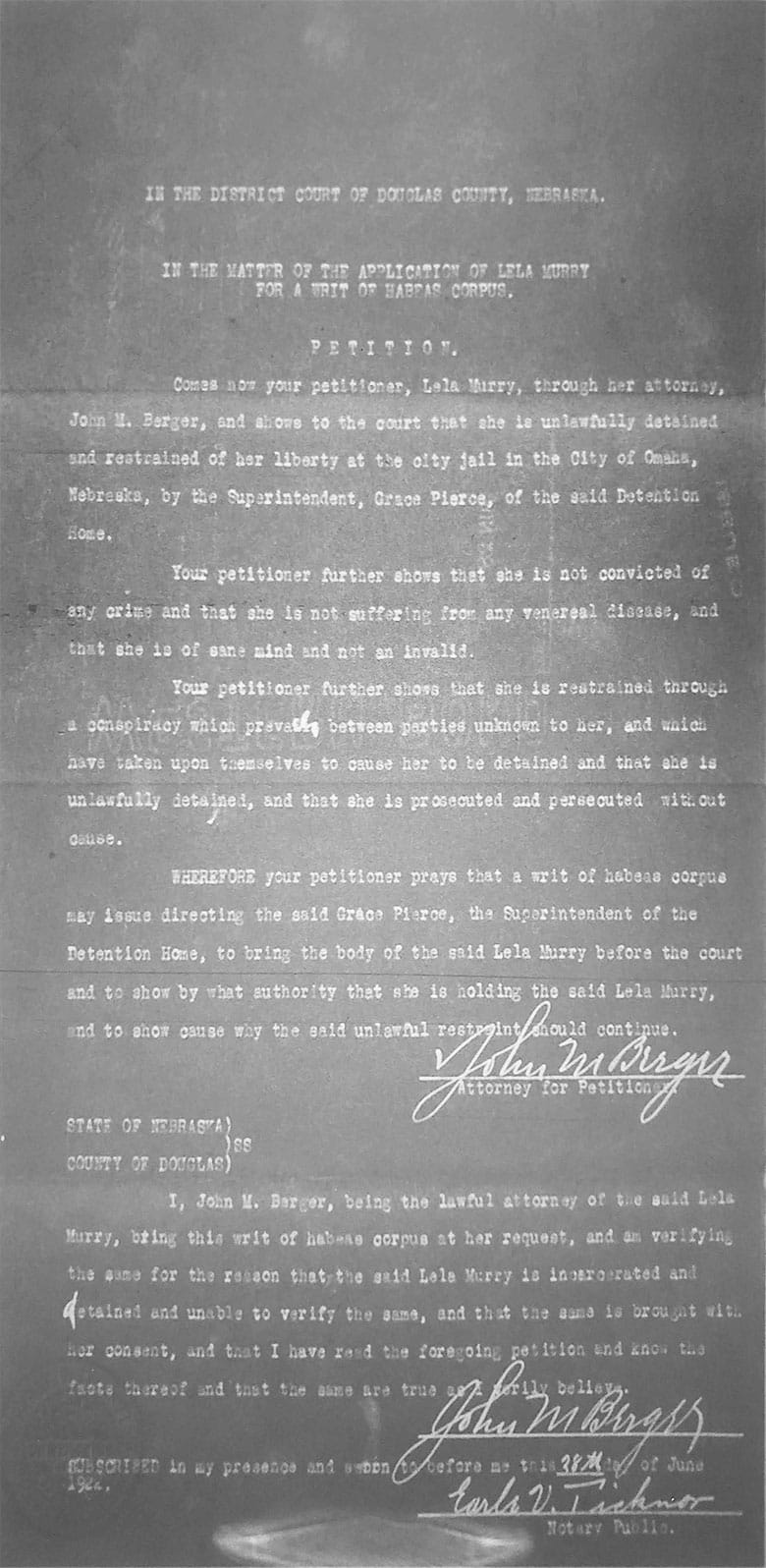

Murry gave birth and lived with her child at the rescue home, receiving assistance until the police arrested her around June 13th of that same year. A subsequent hearing convicted her on charges of prostitution, and the courts remanded her to the Omaha Detention Hospital, where she remained imprisoned until her attorney, John M. Berger, filed a habeas petition on her behalf on June 28th. Throughout her detention, Murry remained unaware of the charges that kept her away from the Salvation Army Home and her infant child. In her petition, Murry maintained that her arrest and detention were the result of a conspiracy against her, by virtue of “unknown persons” affiliated with the Detention Hospital. Murry argued that the police unknowingly convicted her of vagrancy. She asserted that not only was she denied the right to confer with friends and counsel upon her removal from the Salvation Army Rescue Home, but that she was wholly unaware of the nature of the charges brought against her.

Murry experienced an abrupt shift in institutional conditions and treatment when officers forced her out of the Rescue Home. The Omaha Daily Bee exposed the Omaha Detention Hospital (also referred to as the Detention Home) as a site of widespread ill-treatment and corruption shortly before Lila arrived. In 1919, the Omaha Daily Bee published a plethora of scathing reports on the state-ran institute. On January 17, former nurse Wilma Rice launched an attack on Omaha police officers, whom she accused of extorting women on the street, forcing the victims to either make discreet payments or find themselves in the Detention Hospital. Nurse Rice also charged that police surgeons, paid to examine incarcerated women for venereal diseases, gave diseased women a “clean bill of health” upon payment. She also accused them of trafficking girls to madams and potential clients. Furthermore, she claimed she had to pay five officers “hush money” on certain nights to avoid being molested. The scandal prompted calls for reform, and the Detention Hospital appointed a new superintendent, Grace Pierce, on June 1, 1921—about a year before Murry arrived. However, this change in leadership did not prevent ongoing allegations and instances of drug smuggling.

Amidst such extralegal actions, Murry’s confinement at the Detention Hospital was by virtue of the 1916 City of Omaha Ordinance No. 9852, which not only criminalized exposing or communicating venereal infections and viruses, but also authorized the Health Commissioner to “isolate or quarantine any person infected with venereal virus in such reasonable manner and for such reasonable period as to prevent the danger of such person communicating such infection to another.” Murry asserted that she was not suffering from any venereal disease, as the attending physician at the Detention Hospital pronounced her cured and ordered her release. However, the police detained her at the city jail by order of Grace Pierce, the Detention Hospital Superintendent. Murry complained of a conspiracy among “persons unknown to her” at the Detention Hospital, who recommended that she be committed to the State Reformatory for Women at York, Nebraska. Murry and her attorney pointed out that the Magistrate did not issue the commitment to the Reformatory until three weeks after the initial conviction, immediately after she petitioned for habeas corpus. Furthermore, they argued that the Magistrate of the City of Omaha had no jurisdiction to issue a commitment outside of Douglas County, Nebraska, rendering her commitment to the reformatory in York, Nebraska void. Lila Murry has not been located in any records following the conclusion of her petition for a writ of habeas corpus, making hers an incomplete story that links the State Reformatory for Women at York, the Omaha Women’s Detention Hospital, and the Salvation Army Women’s Rescue Home of Omaha as sites of significance in Nebraska women’s Progressive-Era lives.

The State Reformatory for Women at York, Nebraska first opened in 1920 and, like the Omaha Detention Hospital, immediately drew considerable media attention and criticism for poor conditions, and mismanged funds. On January 24, 1922, roughly five months before the courts committed Lila to the facility, the Alliance Herald of Box Butte County published an article that shed light on inhumane conditions within and attitudes towards the reformatory. Myrtle Hetrick and Ruby Fox were inmates at the reformatory, committed on charges of ”incorrigibility.” The women escaped and fled to Wyoming in the summer of the previous year. Not long before they fled, the police captured and returned them to York in 1922. Hetrick and Fox told the Alliance Herald that they preferred the state penitentiary to the reformatory, a rather startling claim given that the latter served as a facility for criminals who committed serious crimes. The girls stated that they could, “tell a plenty concerning the institution at York if we cared to,” but when asked to elaborate, Myrtle Hetrick curtly replied, “let the state tell you.” The many controversies surrounding both State Reformatory for Women at York and the Detention Hospital in Omaha illuminate the conditions in which Lila Murry would have found herself within months of giving birth, and highlight the gravity of her habeas petition.

Despite the urgency of Lila’s cause, a judge did not render a decision until almost two years after Lila filed her petition, and the writ was dismissed “for want of prosecution.” Because Lila Murry has not been located in any records following the conclusion of her petition, the assumption this decision generates is that the petitioner failed to take necessary actions in regard to filing the petition but, given the circumstances of Lila’s case it is difficult to deduce what the reason for this outcome may have been. We can only hope that telling her story here highlights the few options and many difficulties women faced as single mothers in Progressive-Era Nebraska.

Citations

“A Ball at the Blackstone Will Help to Feed and Clothe Fatherless Little Ones.” Omaha Daily Bee. (Omaha [Neb.]) 187?-1922, November 23, 1919, SOCIETY SECTION, Image 14 « Nebraska Newspapers. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn99021999/1919-11-23/ed-1/seq-14/#words=Army+home+Rescue+Salvation.

Fletcher, Adam F. C. “A History of the Salvation Army Hospital in North Omaha.” North Omaha History (blog), January 16, 2019. https://northomahahistory.com/2019/01/16/a-history-of-the-salvation-army-hospital-in-north-omaha/.

Humanities, National Endowment for the. “Inmate of Detention Home Asserts Omaha Men and Boys Support 3,500 Fallen Women,” Omaha Daily Bee. (Omaha [Neb.]) 187?-1922, January 17, 1919, Image 4, Accessed July 28, 2023. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn99021999/1919-01-17/ed-1/seq-4/#date1=1900&index=0&rows=20&words=Rice+Wilma&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Nebraska&date2=1963&proxtext=wilma+rice&y=19&x=21&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

In Re Application of Lila Murry for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, Douglas County District Court, Omaha, NE RG230 (1922). https://petitioningforfreedom.unl.edu/cases/item/hc.case.ne.1316

Omaha, NE., Ordinance No. 9852 (1916).

“Reformatory Is To Be Improved.” The Frontier. (O’Neill City, Holt County, Neb.) 1880-1965, September 01, 1921, Image 6 September 1, 1921. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2010270509/1921-09-01/ed-1/seq-6/.

“Sixty-One Babies Are Born in Rescue Home of Salvation Army.” Omaha Daily Bee. (Omaha [Neb.]) 187?-1922, January 01, 1920, Page 3, Image 3 « Nebraska Newspapers.Accessed July 14, 2023. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn99021999/1920-01-01/ed-1/seq-3/#words=Army+home+Home+Rescue+rescue+Salvation.

“Two Girls Prefer the State Penitentiary.” The Alliance Herald. (Alliance, Box Butte County, Neb.) 1902-1922, January 24, 1922, Image 2, January 24, 1922. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2010270501/1922-01-24/ed-1/seq-2/.

Info on Nebraska Women’s Reformatory at York. https://corrections.nebraska.gov/about/history