Kate Burns married John Lovell in October of 1892. Kate’s marital history had been tragic up to this engagement, as John would be her third husband in six years. She married her first husband in London and they had five children before separating in 1887. In 1890, Kate McGee moved to the state of Washington with her children, and shortly married another man who passed away of unspecified causes in India about six months later. After the death of her second husband, Kate faced tremendous difficulty in caring for her children. On April 1st 1891, Kate (now Kate Burns) dropped off one of her youngest children, Maggie, at the House of the Good Shepherd with their Mother Superior.[1]

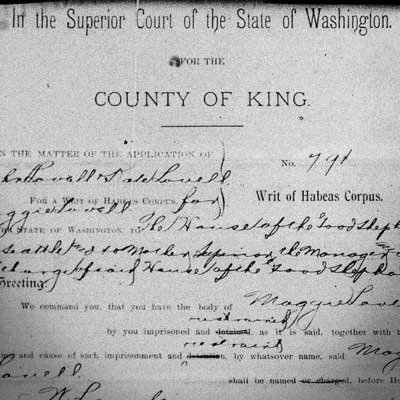

In August of 1891, Kate Burns would return for Maggie in preparation for moving her family to New York. Sister Mary, the Mother Superior of the House of Good Shepherd, refused to surrender Maggie, so Kate filed a habeas petition to challenge the nun. In a hearing on September 12, Sister Mary described Maggie’s poor condition upon being dropped off and Kate’s negative reputation as a mother.[2] Sister Mary also testified that Kate had agreed to place Maggie at Good Shepherd until she was eighteen years old. Kate Burns disputed the Mother Superior’s statement and said she had planned to retrieve Maggie after a couple weeks.[3] Judge I.J. Lichtenberg ruled Kate’s petition invalid, so Kate made a second petition that Judge Lichtenberg also dismissed, calling her an “utterly unfit” guardian of Maggie.[4]

After failing in court, Kate took to the convent directly. A local nurse testified that she saw some Sisters beating Annie McGee, one of Kate’s other daughters, because Annie had tried to grab hold of Maggie with the intention of getting her out of the Home. Kate Burns, who was watching outside of the property’s boundaries, then fought with the Sisters, especially Sister Teresa, to defend her children.[5] The Mother Superior claimed the attack started once Kate Lovell entered the institution’s grounds trying to retrieve Maggie. Maggie allegedly ran in fear away from her mother and towards Sister Teresa for protection. Kate then reportedly beat the Sister until she was “black and blue” and was eventually dragged off the premises by a bystander.[6] Kate was arrested for the alleged assault and later fined twenty-five dollars.[7]

The year did not end well for the single mother, who was arrested again on December 12, 1891, this time for threatening a woman who employed one of Kate’s children as a domestic worker. The employer refused to let Kate Burns see her daughter, which prompted Kate to threaten to “annihilate” her.[8] The case was later dismissed in court, though her reputation as a violent and irritable woman, or a fervent and defensive mother, would further spread and divide her immediate community.[9]

Things improved in the next year for Kate, who married John Lovell, a “frugal, industrious” longshoreman in October of 1892. The new marriage strengthened Kate’s economic and social standing, and in May, 1893 Kate and John Lovell formally declared Maggie McGee their child and had her name changed to Maggie Lovell. With her new legal claim over Maggie, Kate Lovell felt confident in filing a third petition for habeas.[10]

On August 29, 1893, the King County Superior Court and Judge James Weston Langley heard testimony within a crowded courtroom of spectators who anticipated “sensational testimony” in another attempt by Kate Lovell to secure custody of her child. John W. Fairfield, the attorney for Good Shepherd, called several witnesses to describe Kate Lovell’s negative reputation as a mother, including Judge Lichtenberg, who “judicially ascertained” Kate’s reputation and abilities as a mother to be “very, very bad.” Fairfield also questioned John Lovell over child abuse claims that were made against him in July of 1893.[11] Kate and John’s attorneys, William Humphrey and W.F. Hays, found many witnesses who had a positive view of Kate as a mother. Humphrey and Hays also targeted some of the opposing witnesses by suggesting their Catholic affiliation may have colored their testimony in a case involving a Catholic institution: the House of the Good Shepherd. This strategy to highlight bias was a rather shrewd approach. Public opinion surrounding Kate’s reputation made up much of Fairfield’s evidence, while Humphrey and Hays questioned how objective that public opinion could be.[12]

This trial of public opinion stacked the deck against Kate Lovell. To prove herself as a devoted and capable mother, Kate had to fight for her children’s safety, whether it be fighting off belligerent nuns or chastising her children’s invasive employers. Kate faced the many trials of a single mother trying to secure a steady living for her children in a community that looked down upon mothers without husbands. Defending her children so fervently proved her commitment as a mother, but it was a double-edged sword. Kate’s outbursts in defense of her children were extensively used as evidence of her unsuitability as a caregiver for Maggie. Fairfield hardly had to probe witnesses before they shared extensive tales of Kate’s vulgar exploits and negative reputation. What these witnesses left out was that Kate’s actions were most often in defense of her daughters.[13]

On November 15, 1893, Judge Langley ruled against John and Kate Lovell. The Lovell’s quickly appealed to the Washington Supreme Court, initiating the fourth court proceeding in the family’s long saga of trying to reclaim custody of Maggie Lovell. On July 18th, 1894, the Washington Supreme Court found that the “immorality” of the mother should not be a reason to separate mother and daughter, and that the House of the Good Shepherd never made any claim during the original proceeding on why they had legal right to retain Maggie. More specifically, the justices were firm in their conviction that:

It is true that the appellant Mrs. Lovell has not been the most exemplary mother; that the care of her children has not been of that kind which would commend itself to many mothers; that she is a passionate woman with an uncontrollable temper, coarse, vulgar, and pugnacious, is evident from the record; but if every coarse, vulgar, and passionate woman were deprived of the custody of her children our orphan asylums would be filled to overflowing…[14]

The justices recognized the many trials of motherhood, and Kate Lovell, after just over three years, would be reunited with her daughter.

- [1] Katrina Jagodinsky, Cory Young, Andrew Varsanyi, Laura Weakly, Karin Dalziel, William Dewey, Erin Chambers, Greg Tunink. “In the Matter of the Application of John Lovell and Kate Lovell for a Writ of Habeas Corpus.” Petitioning for Freedom: Habeas Corpus in the American West, 1812-1924, University of Nebraska Lincoln. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://petitioningforfreedom.unl.edu/cases/item/hc.case.wa.0874

- [2] “In the Matter of the Application of John Lovell and Kate Lovell,” https://petitioningforfreedom.unl.edu/cases/item/hc.case.wa.0874

- [3] “A Fury’s Outbreak,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer (September 28, 1891): chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045604/1891-09-28/ed-1/seq-8/#date1=1885&sort=date&rows=20&words=Kate+McGee&searchType=basic&sequence=0&index=2&state=Washington&date2=1910&proxtext=Kate+mcgee&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. 8

- [4] “Poor Maggie McGee,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer (August 29, 1893): chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045604/1893-08-29/ed-1/seq-5/#date1=1872&index=3&rows=20&words=Burns+Kate&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Washington&date2=1918&proxtext=Kate+Burns&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. 5

- [5] “For Beating Sister Teresa,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, (October 04, 1891): chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045604/1891-10-04/ed-1/seq-5/#date1=1890&index=6&rows=20&words=Kate+McGee&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Washington&date2=1891&proxtext=Kate+mcGee&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. 5

- [6] “A Fury’s Outbreak,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer: 8

- [7] “Mrs. Burns Failed to Appear,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, (November 05, 1891): chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045604/1891-11-05/ed-1/seq-5/#date1=1865&index=13&rows=20&words=Burns+Kate&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Washington&date2=1963&proxtext=Kate+Burns&y=8&x=15&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. 5

- [8] “Mrs. McGee Arrested,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, (December 12, 1891): chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045604/1891-12-12/ed-1/seq-2/#date1=1890&index=14&rows=20&words=Mrs+Reynold+Reynolds&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Washington&date2=1892&proxtext=Mrs.+Reynolds&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. 2

- [9] “Brevities,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, (December 15, 1891): chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045604/1891-12-15/ed-1/seq-5/#date1=1890&index=10&rows=20&words=Kate+McGee&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=Washington&date2=1891&proxtext=Kate+mcGee&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. 5

- [10] “In the Matter of the Application of John Lovell and Kate Lovell,” https://petitioningforfreedom.unl.edu/cases/item/hc.case.wa.0874

- [11][11] “In the Matter of the Application of John Lovell and Kate Lovell,” https://petitioningforfreedom.unl.edu/cases/item/hc.case.wa.0874

- [12] “Poor Maggie McGee,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer: 5

- [13] “Poor Maggie McGee,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer: 5

- [14] “In the Matter of the Application of John Lovell and Kate Lovell,” https://petitioningforfreedom.unl.edu/cases/item/hc.case.wa.0874